This talk was reprinted as "Beyond the golden parachute" in Harper's magazine.

It's an honor to be here in Tampere, addressing this audience of the most outstanding textile workers in the world today.

Looking around at this diverse sea of faces, I see outstanding elements of corporations like Dow, Denkendorf, Lenzing, all at the forefront of consumer satisfaction in textiles. I see members of the European Commission, Euratex, and other important political bodies that aim at easing rules for corporate citizens. I also see professors from great universities walking into a prosperous future hand in hand with industrial partners, using citizen funds to develop great textilic solutions to be sold to consumers for profit and progress.

I see on all of your faces a touching, childlike eagerness to tackle the biggest textiles questions today. At the same time I see a deep understanding that some of these solutions may not be easy, but that come what may, we have to press on into a future that few of us understand, except in terms of its dollar results.

How do we at the WTO fit in? Well, that's easy: We want to help you achieve those dollar results. When roadblocks to dollar results arise--protectionism, worry, even violence against physical property--we want to help make sure that none of this stands in the way of your dollar results.

What do we want? A free and open global economy that will best serve corporate owners and stockholders alike. When do we want it? Now.

Of course, just like nature, the market sorts things out by itself. It's like Darwin said, if you look at nature, one thing is clear, and that's that things go well--and that if you apply natural laws to human society, things will go well too.

But like all of us--even wild animals--the market can use some help. And we at the WTO are committed to providing that help, to helping the market help those that need it the most.

We're using a variety of techniques to do so.

Lobbying for example, and other political tactics.

Also "guerrilla marketing" and other corporate techniques, to cleverly show teenagers the value of liberalization; and so on.

Finally, we have in mind some far more sophisticated and advanced solutions.

Some of these solutions are based in textiles. In just twenty minutes from right now, I'm going to unveil the WTO's very own solution to two of the biggest problems for management: maintaining rapport with a distant workforce, and maintaining healthful amounts of leisure. This solution, appropriately enough, is based in textiles.

But how did workers ever get to be a problem? Before unveiling the solution, I'd like to talk a bit about the history of the worker/management problem. We will follow the stages of work from pre-industrial to an imported workforce model, from an imported workforce to a remote workforce model, and finally--the stage we're going through now--from a remote workforce model to a remote workforce that really works. And incidentally, we'll see that at every step of this evolution, it is textiles that has played the central role.

The first leg of our management-historical journey is back to 1860s America, and the U.S. Civil War. We all know about this war--the bloodiest, least profitable war in the history of the U.S., a war in which unbelievably huge amounts of money went right down the drain--and all for textiles!

Of course, this war is most famous for having effected a mighty change in the management paradigm from a central-owner hierarchical model to a much more decentralized, fluid model--a real "hippie revolution" kind of paradigm shift!

We'll talk about this misunderstanding in a moment--but first, a bit of background.

Believe it or not, even many Americans don't know what caused the Civil War. Why did people fight and die and lose money? The answer is really really simple, but it is surprising.

It comes down to one word: FREEDOM.

By the 1860s, the South was utterly flush with cash. It had recently benefitted from the cotton gin, an invention that took the seeds out of cotton and the South out of its pre-industrial past. Hundreds of thousands of workers, previously unemployed in their countries of origin, were given useful jobs in textiles.

Into this rosy picture of freedom and boon stepped... you guessed it: the NORTH.

The South, of course, wanted to buy industrial equipment where it was cheapest, and to sell raw cotton where it fetched the highest price--in Britain. The North, however, decided the South should NOT have the FREEDOM to do this, but instead should HAVE to do business with the North, and only with the North.

The North used its majority stake in the country's governance to exploit the Southern landowners and deny them their freedom to choose the cheapest prices; this of course made them very angry. You'd be angry too if you were denied your freedom of choice! And so the North's abusive tariff practices basically caused what otherwise was a perfectly good market to spiral into a hideously unprofitable war.

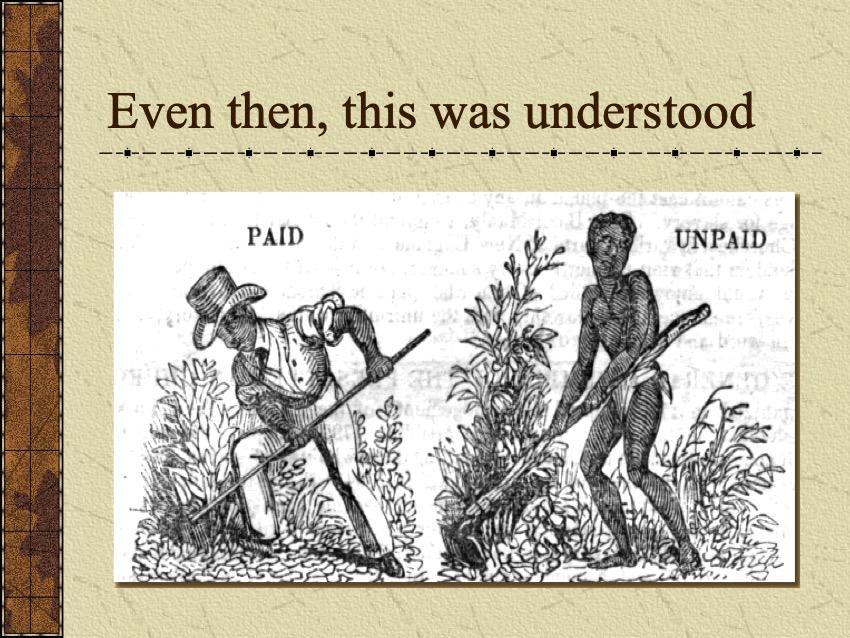

Now some Civil-War apologists have said that the Civil War, for all its faults, at least had the effect of outlawing an Involuntarily Imported Workforce. Now such a labor model is of course a terrible thing. I myself am an abolitionist. [if laugh--"not that it makes much difference now!"] But in fact there is no doubt that left to their own devices, markets would have eventually replaced slavery with "cleaner" sources of labor anyhow.

To prove my point, come join me on what Albert Einstein used to call a "thought experiment". Here: Suppose Involuntarily Imported Labor had never been outlawed, that slaves still existed and that it were easy to own one. What do you think it would cost today to profitably maintain a slave--say, here in Tampere?

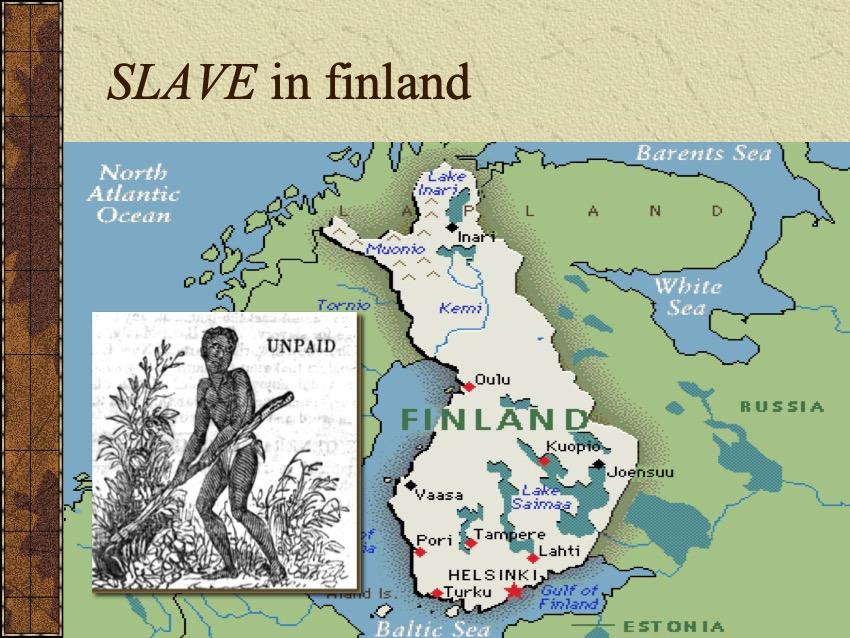

Let's see.... A Finnish clothing set costs $50 at the very least. Two meals from McDonalds cost $10 or so. The cheapest small room probably runs for $250 / month. To function well, you have to pay for your slave's health care--if its country of origin was polluted, this could get very expensive. And of course what with child labor laws, much of the youth market is simply not available.

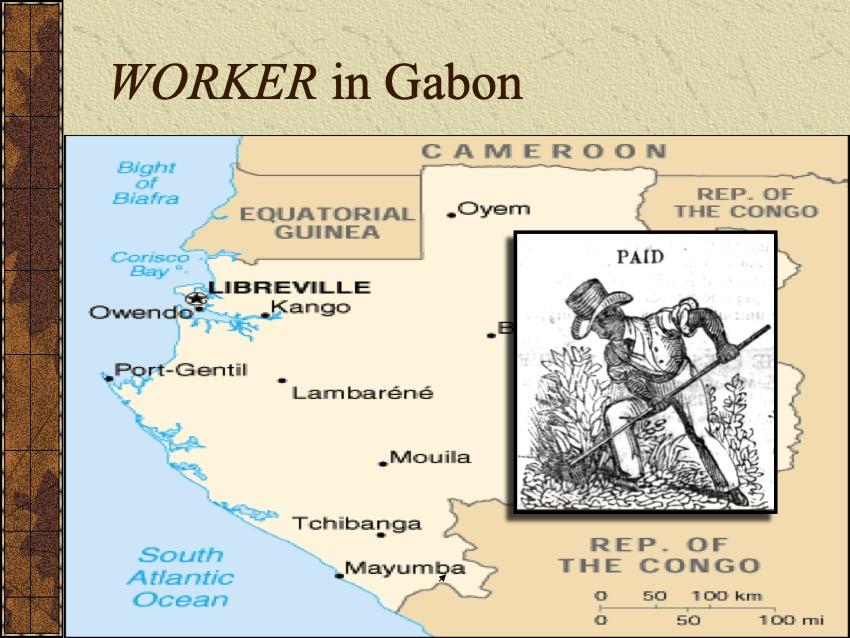

Now leave the same slave back at home--let's say, Gabon. In Gabon, $10 pays for two weeks of food, not just one day. $250 pays for two years' housing, not a month's. $50 pays for a lifetime of budget clothing! Health care is likewise much cheaper. On top of it all, youth can be gainfully employed without restriction.

The biggest benefit of the remote labor system, though, is to the slave--because in Gabon, there is no need for the slave not to be free! This is primarily because there are no one-time slave transport costs to recoup, and so the potential losses from fleeing are limited to the slave's rudimentary training. So since the slave can be free, he or she suddenly becomes a worker rather than a slave! Also terrific for morale is that slaves--workers!--have the luxury of remaining in their native habitat and don’t have to relocate to places they would be subject to such unpleasantries as homesickness and racism.

Is there any competition between these two models of life, for either side?

I think it is clear from this little thought experiment that if the North and South had simply let the market sort it out without protectionist tariffs, they would have quickly given up slavery for something more efficient anyway. By forcing the issue, the North not only committed a terrible injustice against the freedom of the South, but also deprived slavery of its natural development into remote labor.

The WTO is fortunately not alone in understanding the power of the market to resolve serious issues. I quote president George Bush on this issue. At the Quebec FTAA meeting he said: “Free and open trade reinforces the habit of liberty that sustains Democracy over the long haul.” Had the leaders of the 1860s understood what our leaders understand today, the Civil War would never have happened.

Now the "modern" remote labor model, while much better than the imported workforce model, is--being decentralized--also much more complicated from a management perspective.

In a world where the headquarters of a company are in New York, Hong Kong or Espoo,

and the workers are in Gabon, Rangoon, or Estonia, how does a manager maintain proper rapport with the workers, and how does he or she ensure from a distance that workers perform their work in an ethical fashion?

Let's look at a counterexample--a case in which managers remained out of touch with remote workers, leading to extreme worker dissatisfaction and the eventual total loss of the worker base. Perhaps we can learn from this case and avoid such catastrophes in the future.

In 19th century Britain, just like in the South, things had never looked better. The country was flush with cash and potential and freedom, thanks to new technology--the spinning jenny. Like the cotton gin in the South--for turning raw cotton into useable cotton--Britain's spinning jenny turned useable cotton into finished textiles, so the British could suddenly mass-produce clothing.

Like in the South, all that was needed was a workforce to produce the raw materials that these new tools required. The British, being more advanced, took a modern approach: instead of expensively importing workers, they located their employment opportunities where workers already lived: India.

There were problems, right from the start. For thousands of years India had made the finest cotton garments in the world--so Indian workers felt humiliated when they had to just provide raw materials to British industry.

The main rabble-rouser--literally--was Mohandas Gandhi, a likeable, well-meaning fellow who wanted to help his fellow workers along, but did not understand the benefits of open markets and free trade. Gandhi thought that through "self-reliance"--protectionism against textiles trade with Britain--India could become strong and relearn its own ancient ways of textiles.

These rather naive ideas became extremely popular, and a big proportion of the citizenry rose up against the British management system. The British eventually had to leave!!!

So what are the lessons for management here? The big problem in India was clearly a grave lack of management rapport with workers. By making only small adjustments, British management could have kept India on the path to modernity.

For example, one of the things Gandhi and his anti-globalization followers did was make their own clothing at home, to symbolize their independence from the cotton trade that they perceived as imposed and oppressive. Now as any student can tell you, if management in England had been properly in touch with worker concerns, they could have responded in a timely way--e.g. by making available clothes in the home-spun style that the Indians craved. Today you can see clothes like that in many clothing catalogues, like the Whole Earth Catalogue, for example.... But of course they didn't have that sort of perspective in Britain and so they couldn't do it.

India still has a long road to recovery from Gandhi's legacy of protectionism. Bill Gates really summed it up on his recent visit to India when he said, "India faces big challenges, such as the existence of well-meaning laws that hinder entrepreneurs. For example, there are laws that say people can't be laid off and that companies can't go bankrupt. As its technological, political, and economic systems are modernized, India's progress will accelerate."

Now while the British may be excused for losing India because of a want of technology, we have no such excuse. In these sensitive times when a large percentage of the world's population is nearing the boiling point over problems they imagine with globalization--when much of the world may be feeling as Gandhi felt, and may be on the point of taking drastic measures--we need to use all resources at our disposal to help the market help corporations, to assure that things go well--in society just as in nature.

Again, we need to use all the political tools at our disposal.

And again, marketing to certain population sectors can change future perceptions. The market--in the form of privatized education--is likely to be our ally in this process of shifting children's awareness from less productive issues and thinkers to more productive ones, but we can help it along as well.

But even more important than any of this is management's on-the-ground efficiency. To avoid another India, we must insure that management is constantly in touch with workers, but constantly, and not just intellectually but by all the tools at our disposal--i.e. the senses. So that the manager has direct, visceral access to his or her workers, and can experience their needs in a visceral way.

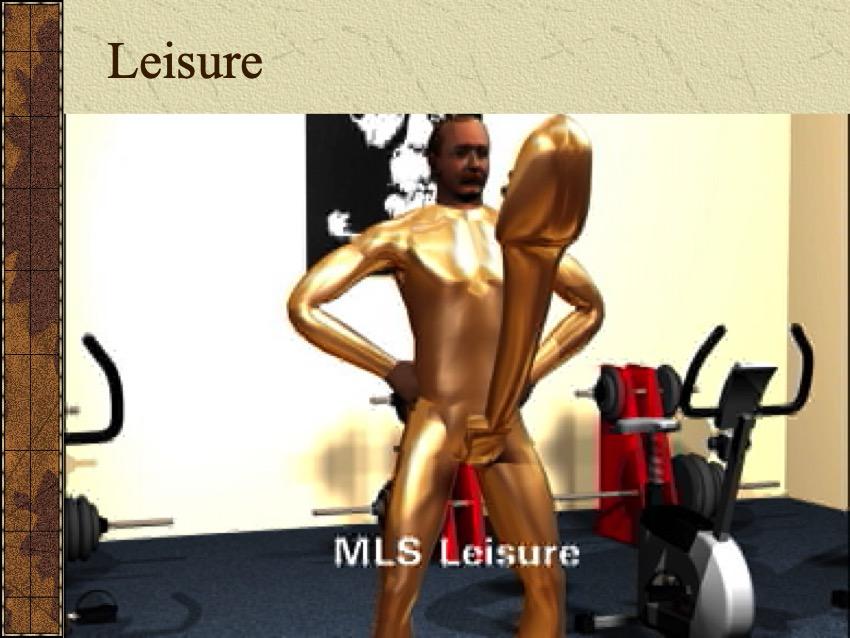

Now I'm about to show you an actual prototype of the WTO's solution to two major management problems of today! There are some video spots that accompany it--and I just want to say that you know, sometimes things don't turn out quite as you imagined they would--sometimes you give something to an agency and it just comes back a little different from what you expected. The animators went a little too far in some parts--I think you'll see which parts....

And a second thing I wanted to say is--this design isn't necessarily to be taken literally. This is more important as a direction, really--to get you thinking outside the box on solutions to management problems... so you can start imagining a more holistic way of answering the call of management's many challenges.

Now we all know that not even the best workplace design can help even the most astute manager keep track of his workers.

You need a solution that enables a lot more rapport with workers--especially when they're remote.

Mike, would you please?

[Mike rips off Andy's business suit.]

Ah! That's better! This is the Management Leisure Suit.

This is the WTO's answer to the two central management problems of today: how to maintain rapport with distant workers, and how to maintain one's own mental health as a manager with the proper amount of leisure.

How does the MLS work--besides being comfortable? Well, allow me to describe the suit's core features.

[Andy inflates the EVA, takes off the underwear, inflates the butt]

This is the Employee Visualization Appendage--an instantly deployable hip-mounted device with hands-free operation, which allows the manager to see his employees directly, as well as receive all relevant data about them.

Signals communicating exact amounts and quality of physical labor are transmitted to the manager not only visually, but directly, through electric channels implanted directly into the manager, in front and behind. (The workers, for their part, are fitted with unobtrusive small chips that transmit all relevant data directly into the manager.)

The MLS allows the corporation to be a corpus, by permitting total communication within the corporate body (on a scale never before possible). This is important--but the other, equally important, achievement of the MLS has to do with leisure.

In the U.S., leisure--another word for freedom, really--has been decreasing steadily since the 1970s. The MLS permits the manager to reverse this trend by letting him do his work anywhere--all locations are equal.

Now the MLS is good for both managers and workers, but the number of non-corporate solutions, also, is as endless as our imagination. For the WTO, for example: with the MLS I'll be able to not only see protests right here, but I'll be able to feel what's going on in the hot spots of the world. What will the danger level be when the first protester is beheaded? I'm against beheading, but they do that in Qatar, where we're holding our next meeting. The MLS can in a general sort of way show us things--it can help us discover new metrics.

In conclusion, this suit--is it a science-fiction scenario? No--everything we've been talking about is possible with technologies we have available today.

And even more interesting solutions are being developed everywhere. Right here, today and tomorrow, we will be learning about many of these very technologies I've been discussing from the prime movers themselves. Interactive textile materials, adaptable materials for smart clothing, living shirts that monitor the wearer's vital signs and motion.... The very people pioneering these remarkable tools will be telling us about them.

Also here, and of equal interest, are the regulators, trade officials, and others who make the world go round-- my colleague Pertti Nousiainen of the European Apparel and Textile Organization, whom I have the pleasure to follow, and my colleague Erkki Liikanen of the European Commission, who will show us tomorrow how traditional industry can be made more useful to the global economy, and who will show us the importance of always looking forward on the highways of progress towards ever new horizons, with cooperation and mutual delight in the fruits of prosperity.

I am very excited to be here. Thank you.

[There were no questions.]