This lecture was delivered in March 2002 by “Dr. Kinnithrung Sprat” to a large class of university students at the State University of New York at Plattsburgh, as a dress rehearsal for a lecture in Sydney (which Mike and Andy changed entirely after the reaction to this lecture). As Dr. Kinnithrung Sprat began to speak, a corporate representative from McDonald's (Mike Bonanno), passed out hamburgers to all the students.

Hello to all in this wonderful place! I would like to begin by thanking the Economics and Design Schools for inviting us here to impart to their student clientele just a hint of the wealth of knowledge contained in the vast, great field of what we like to call “Business Without Barriers,” in all its manifold complexity.

Thanks to all you student clientele, too, for coming with us on our mission. Yes, mission: trade liberalization is, truly, a religious undertaking, a project of faith, a crusade of sorts—and it has been ever since its founders declared that financial success comes from God, that wealth is a sign of divine favor. Today we like to make liberalism sound scientific, and pretend that it’s more a matter of fact than of faith, but it’s only by remembering the divine nature of our convictions that we can fully maintain them.

I’d like to thank as well our corporate sponsor, McDonalds, who is generously providing the refreshments. Mike Bonanno is passing them out; Mike is Public Relations Officer for McDonald’s for the North New York region. Thank you, Mike! Finally, thanks to the traditional owners of the Plattsburgh region, the aboriginal Mohawks. And today, as it happens, I’m going to unveil an ambitious new plan to help all of the world’s downtrodden—yes, including aboriginal New Yorkers!—to integrate more effectively into the global marketplace, conquering excessive hunger while in the process enriching us all.

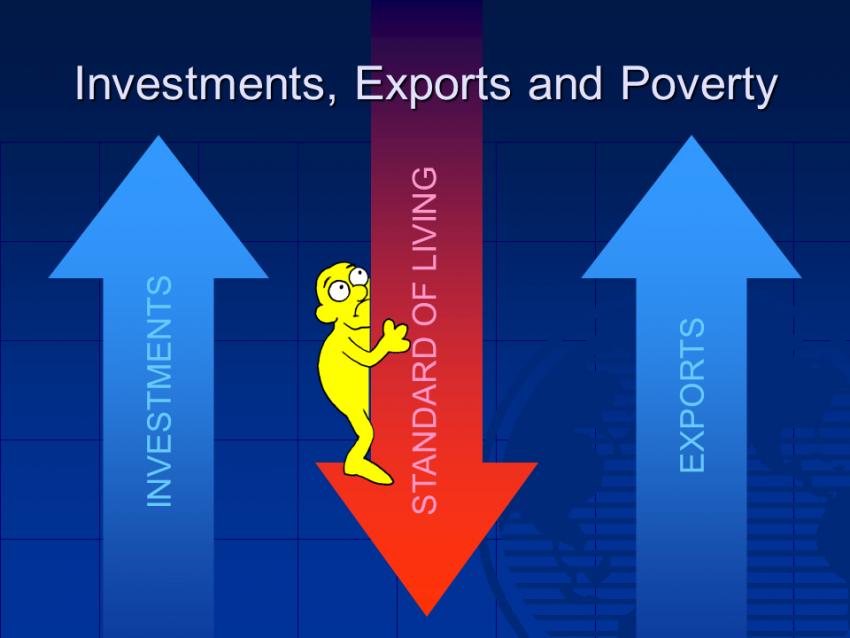

Now let’s start right at the beginning, with the main question: why is Third-World starvation a problem? First, the facts. As we all know, investment and exports have been on the rise in the Third World. In 2001, First World enterprises invested three times more money into Third-World projects than they had ten years earlier. Third-World exports have increased at a similar breakneck pace. Yet despite this flourishing of trade, there are now 50% more desperately poor people in the world than just 20 years ago! Inequality has doubled in the same period. As a result, almost half the world’s population now lives on less than $2 per day.

Because of the rise in poverty despite increased investment and trade, a growing percentage of people suffer from food-insufficiency diseases like marasmus, kwashiorkor, marasmic kwashiorkor, nutritional dwarfism, etc., whose symptoms include lethargy, inability to work, a host of ailments physical, mental and spiritual, and of course early death. In some places in Africa, for example, fully 80% of the youth population is malnourished in this way! This kind of situation creates huge problems in the First World. Why? Because every day in which people don’t consume food is another day in which they don’t participate fully in the global trade that makes us all better off.

“The poor are the customers of the future,” as our Director-General has said—and right now, starvation makes that future ever so distant! We must quickly find solutions to famine and debilitating death, to help these troubled populations become useful members of the booming import-export-investment economy.

Bear with me please. In a few minutes, I’m going to unveil the WTO’s own proposed solution to hunger. But first, to help you understand why it’s the only real solution, we’ll begin by looking at other proposed solutions to hunger, and we’ll see why they’re completely unacceptable.

To understand these proposed solutions, we must understand the mechanisms behind Third-World famine today. In today’s world, it turns out that famine is entirely within human control.

It rarely results directly from drought, flooding, disease, or conflict, as the popular media would have us believe, but most often happens simply because people do not have enough money.

During the Irish Potato Famine, for example, there was plenty of food in Ireland, and rich Irish landowners exported many shiploads of it to English consumers. But one million Irishmen starved to death because they couldn’t pay for it.

Today’s agribusiness companies, like the wealthy Irish farmers, use a variety of means to monopolize a country’s land for a single exportable “monocrop”—rice, soybeans, corn... or potatoes.They make it very lucrative for wealthy farmers with a lot of land to convert to the new export crop, and these wealthier farmers then buy out their neighbors. Eventually all the good land is used for the single export monocrop, and everyone works for the wealthiest farmers.

Before, everyone grew a few different crops, not just one—so that when one crop failed, there were always others to maintain the population in life.

The new single crops, however, can be lost all at once to disease, like the potatoes in Ireland, or to a lack or excess of rain. Many famines result from this. More commonly, however, they result from price fluctuations. With the best land monopolized by the one export crop, people depend on the ups and downs of the global food industry, rather than on their own plot of land. When the trading price of a monocrop falls due to increased competition, thousands of workers lose their jobs or receive lower wages. Without an alternative food source—all land being used for the monocrop—huge numbers of poor people starve to death.

Nearly all Third-World countries have been opened for business by First-World companies. Healthy competition like that brings lower prices; so price-based starvation—sometimes slow, sometimes fast—has come to dominate much of the world.

Fortunately, in the worst money-lack situations, our colleagues over at the IMF and World Bank provide loans. These loans can temporarily reduce the starvation death that accompanies growth and openness and modernity. But to receive such a loan, a borrowing country must further open its doors to global agribusiness—which sadly leads to a bit more death along the difficult road to prosperity.

Now it’s all too easy for non-specialists to be blinded by the fact that First-World corporations—by replacing local modes of subsistence with monocrops and exposing vulnerable populations to the vagaries of the global marketplace, not to mention the weather—are technically responsible for so much starvation and death in the Third World.

This is one of those “false truths” we all know so well, that leads well-intentioned people—the Zapatistas, the Via Campesina and Vandana Shiva crowd, the World Development Movement—to call for restricting big agribusiness through tariffs, export limitations, etc.

These people think that if corporations were prevented from doing whatever they wanted in Third World markets, the land would return to meeting local nourishment needs rather than enriching elites at home or abroad. With lucrative export options reduced, they say, small local markets would flourish again, and farmers would again grow a few crops instead of just one, enhancing the likelihood that some would survive even in drought or flood or bad-market conditions.

Now God Himself knows these “limit-the-rich”-type solutions all sound good. But regardless of whether they could conceivably get rid of starvation, they all have some extremely fatal problems, that make them all 100% no-go solutions.

The first problem with export-limiting, tariff-imposing solutions is, they’re culturally insensitive. Imagine you’re a culture whose legacy includes giving the world its first planted field, its first seed bank, its first herd of domesticated animals. Now imagine that the rest of the world has developed these techniques to exciting new heights, and that it has involved you in the lucrative new markets that result. Wouldn’t you be insulted if people suggested you should withdraw from these markets and go back to growing your food for survival, rather than the export enrichment of your best citizens? Maybe it’s this sort of cultural insensitivity that makes the richest, most powerful citizens in these countries so indignant at proposals to limit First-World agribusiness in Third-World markets. What’s the potential benefit of such protectionism? Getting rid of a bit of starvation. What’s the cost? Nothing less than missing out on the forward march of humanity.

One theory holds that if Third-World economies were more focused on meeting local needs, getting rich through export would be harder, and the poor—with better land and growing opportunities—would become somewhat less poor. The difference between rich and poor would diminish.

Now this might sound very good—but unfortunately, as we all know, the modern corporate economy depends on the rich/poor divide! These poor, you see, spend their money on living; they can’t invest very much. If the poor and middle class own 95% of the country’s wealth, only about 15% of that wealth can go to financing corporate growth.

The rich, on the other hand, can invest tons without going hungry. If the rich own 95% of the wealth, fully 70% goes to financing corporate growth. And the less they are taxed for programs like education and health, the more that figure increases! As we know from our free-market classes, this equation spells good times for everyone.

There’s one last problem with keeping big agribusiness out of Third-World markets. The people who want to solve hunger this way just don’t understand free-market theory. In 1786, the great English economist Joseph Townsend, sometimes called the grandfather of modern neoliberal economics, spoke about the basis for free-market capitalism.

Hunger will tame the fiercest animals, it will teach decency and civility, obedience and subjection, to the most brutish, the most obstinate, and the most perverse.... It is only hunger which can spur and goad [the poor] on to labor... Hunger is not only a peaceable, silent, unremitted pressure, but, as the most natural motive to industry and labor, it calls forth the most powerful exertions. (An Essay on the Poor Laws, Joseph Townshend, 1786)

In other words, in society just as in Nature, hunger helps. If some people are to some degree hungry and dismal because of their failure to keep up, others, seeing this, will be invigorated to excel. People’s overall energy level will be boosted, as will their tolerance for difficult work situations. Hunger is the foundation of free-market theory, and therefore of progress itself. Eliminate hunger permanently and you threaten the solidity of the worker base, the edifice of the market, and the upward swing of all civilization.

We can see what happens when Townsend’s “hunger help” model is forgotten. Several First World countries, and even some in the Third World, have a minimum allowance for everyone, whether homeless, worthless, criminal, stupid, or lazy. Anyone can receive a monthly allowance, in perpetuity, to ensure that he or she eats sufficiently to survive to a ripe old age. But compare the GNPs of the Netherlands, or of Cuba, with that of the USA—you’ll see that no-hunger solutions are a sure loser!

Now you’ve all taken the right college courses. So I don’t even have to tell you the correct answer to the conundrum of excessive starvation death in the Third World. You know, and I know, that as always, the correct answer is simply: the market. And as you probably know, there is, already, a market system that works against hunger. It comes from today’s “hunger-help” capital: the good old US of A.

Now it’s common knowledge that in America, a large proportion of the population is impoverished—and at levels often like those of the poorest Third World countries! But it’s seldom malnourished! More precisely, it doesn’t suffer from debilitating, work-impairing diseases like marasmus, kwashiorkor, marasmic kwashiorkor, nutritional dwarfism, etc.

In fact, the US poor tend to have food-overabundance problems—sleep apnea, diabetes, hypertension, coronary diseases, gallstones, pseudotumor cerebri, etc.—problems which are not usually lethal to work. And this happens with the help of the market, driven by hunger—not by getting in the market’s way!

To what can we attribute this miracle? Well, many of you will now find the answer right in your stomachs: fast food. Until the 1950s, many poor Americans grew their own food as they were able, engaging in outside-the-market sorts of backbreaking food production—the same sort as still flourishes in a few last corners of the Third World.

In today’s USA, these sorts of food production have been replaced with the infinitely more efficient fast food industry, which enables the US poor, for a tiny $5 daily investment, to keep themselves relatively alive, with only minor side effects.

For an example of what happens when the fast-food market hasn’t been free to provide for a populace, we can again look to Europe. In the early 1900s, the French pseudo-science of “puericulture” taught mothers to measure their children’s portions and watch carefully for weight gain.

Fast food was strongly discouraged both through law and education. Today the French poor may live much longer than in the US, but the GNP? Well, enough said! You don’t see anyone buying up francs!

The world is a very complicated place, and we can’t just take a solution that works miracles in America, transplant it to the Third World, and expect it to do miracles there. The reason is poverty. Whereas the US poor can keep themselves large for about $5 in fast food per day, even the minimum $1 per hamburger per day is far more than can be afforded by today’s Third-World “problem populations” with the wages they make from production of monocrops—under $2 per day in most of the world!

Some feel that eventually the poor will have more money, enough to buy enough hamburgers to survive on—but clearly that is a long way off, given the fact that income is currently going down. Some others, seeing the problem, focus on the self rather than on the sufficiency, as it were: they suggest reducing the food-intake needs of the poor through surgery.

Needless to say, we at the WTO find such solutions reprehensible, to say the least. Surgery permanently alters its subject; these altered, de-hungried consumers remain half-dead to the market, unfit for consumption—even when the market revives.

Also, surgical solutions are culturally very insensitive, and rely on bureaucratic higher-ups—skilled surgeons or geneticists rather than lazy government and U.N. officials, but meddlers nevertheless. Socialistic people-alteration solutions do solve the problem of starvation, and do have the virtue of freeing capital for where it can best nourish the economy, i.e. the rich. But that is where the advantages end.

Fortunately, there is a much better way to adapt poverty-stricken, monocrop-dependent populations to the level the global agribusiness market has chosen for them—a way that solves the problem of debilitating death without disabling wealth-driving consumption or hunger: a market-based way.

Now on our long march of progress, we’ve often heard that old refrain: “Oh, you can’t do that, it’s not right, it violates human rights.” We heard this at every stage of 19th- and 20th-century industrialization, with every improvement in worker-management efficiency, etc. We even hear it today! But are things so simple in the human-rights realm?

Let’s not forget that until 150 years ago, there was no concept of human rights for factory workers. They simply needed to “work their way up” the evolutionary ladder. Today we have lost this empowering vision, and we saddle Third-Worlders with a concept of what it means to be human that is out of all measure with history, and this slows down their progress towards the levels that we have arrived at.

Clouding the picture even further is the report from science. Studies conducted on those working twelve-hour days at repetitive tasks show vital patterns that resemble those of hamsters rather than humans. Given that much of the Third World is subject to this sort of lifestyle, can we afford to ignore the question of biological category when evaluating human rights for these people? (Hamsters are terrific, and deserve to be treated very well—but do they deserve human rights?)

As we consider these questions, it behooves us to remember the pragmatism of former World Bank Chief Economist and current Harvard University President Lawrence Summers with regard to a similar problem:

Just between you and me, shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging more migration of dirty industries to the LDCs [less developed countries]?... The economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable, and we should face up to that... Under-populated countries in Africa are vastly under-polluted; their air quality is probably vastly inefficiently low compared to Los Angeles or Mexico City... The concern over an agent that causes a one in a million change in the odds of prostate cancer is obviously going to be much higher in a country where people survive to get prostate cancer than in a country where under-five mortality is 200 per thousand.

Summers understood the need to consider more than obvious, superficial concerns in evaluating our impact on Third World countries. This sort of pragmatism prepares us well for understanding the only solution that can solve Third-World starvation without interfering with today’s market mechanisms.

Now we in the First World are quite used to the idea of recycling—those big green bins and all. Most of us don’t take it very seriously; we seem to know that the target of recycling—individual consumption of non-edible industrial products—is a tiny part of the problem. But there is another kind of recycling as well: recycling what counts, where it counts. To begin to understand the theory behind this, you must first realize that the human body is not very efficient.

When ingesting heavy foods, only about 30% of the nutrients are absorbed by the alimentary passageway, while the other 70% finds itself expelled in post-consumer byproducts.

Already 20 years ago, NASA scientists tapped into this nutritional gold mine by developing filters to transform their astronauts’ waste into healthy, hygienic, and even delicious food once again.

With the use of this technology, a single hamburger, for example, can be eaten more than ten times, providing a cumulative total of three times the nutritional value of the original “fresh” hamburger.

This technology has proven successful in the commercial sector already. For the past two years the McDonald’s Corporation, a leader in private-sector research, has been including 20% to 30% post-consumer waste in certain of its products—including the hamburgers you have just savored.

McDonald’s has even introduced 100% recycled versions to some Third-World markets, where they hope to appeal to consumers who like hamburgers but cannot afford fresh ones.

Now, to reach consumers even poorer than those, the WTO and McDonald’s together have developed a version of this technology that is so simple and low-cost that it can be distributed for free directly to target populations throughout the Third World.

This filter— dubbed the Personal Dietary Assistant (PDA), and about the size and shape of a coffee filter—will enable consumers to decide for themselves just how many times to evolve their results, according to their own particular needs. The WTO’s goal is get PDAs to two billion needy consumers in the next five years.

More “Robin Hood,” I’ll bet you’re thinking. Just giving things away for free. Well, in fact, no. The PDA is not only as cheap to produce as a single cupful of rice (again, it’s really just a glorified coffee filter), it is also a one-time investment, for it can be reused almost indefinitely. Even better, recycling will eventually lead to full, normal consumption patterns within a fully modern market. How so? Simple.

While a PDA user will be able to safely extend the life span of a hamburger by as much as a factor of ten, the taste advantages of the recycled product will decrease each time the technique is applied. Even a once-recycled hamburger is not quite as appealing, in a marketplace sense, as the original, unevolved item—though I think you’ll agree that the taste is hardly distinguishable.

Since everyone naturally strives for the very best-tasting product they can afford, users will do all they can to maintain a diet as near to fresh as possible. So people will “let go” of a hamburger as soon as possible—after three recycling cycles, say, rather than four. (By selling their recycled product to those who cannot yet afford higher quality, those who can will be able to bolster their financial income—by the seat of their pants, as it were.)

With everyone trying to opt out of re-eating, the culture gravitates towards the full global market in all its freshness—which doesn’t happen with crippling socialistic solutions like protectionism or digestive-tract surgery. But the benefits of widespread recycling technology will be clear even before any market recovery goals have been met.

In Australia, for example, there is a situation where lucrative weapons-grade uranium mining is destroying the food and water sources of various indigenous peoples. With the PDA and fast food, these aborigines will no longer depend on the land for survival, and will be able to profit from uranium mining as is their birthright.

This will make for a real win-win, “food and bombs” situation! And if the First World, for its part, finds the feel-good food-aid habit just too hard to break—well, exporting our higher-quality, nutrient-richer consumer byproducts to “problem populations” for recycling could be the most humane form of assistance possible.

I’d like to conclude here with a few words on openness. One of the principal beauties of the recycling solution is that it integrates well into the current market situation of these cultures—it is culturally sensitive. We can foresee being able to seamlessly insert it into the culture; in exchange, as it were, the culture will insert itself seamlessly into the market. Yet no matter how culturally sensitive recycling is, it is essentially a trait that is alien to the culture. It is a sort of cultural graft—foreign, imposed. The next big challenge, and the far greater one, will be to tap into the profit potential of traits that already exist, and to respectfully leverage the existing cultural infrastructure in the healthy pursuit of profit.

One possible example comes from right here in upstate New York! You may know about Native American elders going off to die alone so as not to burden the group. This is very touching, but it is also a live, untapped field for profitability.

The human body, even near death, produces material worth thousands of dollars, cash that could substantially aid a dying elder’s kinship group. Would this not be a more productive behavior, while remaining within the same spirit?

On a national scale, the IMF estimates lifesaving loans based on the resources that a country has—resources that can be exploited by First-World companies. If the human organism with its immense natural bounty can factor into this equation, how much more loan-worthy a country becomes! The well-utilized citizen thus becomes a factory for the global economy, and thus for the future of his or her country.

To inspire us in appreciating and uncovering such potential gold mines that lay hidden deep within native cultures, I’d like to close by quoting two bits of history: one from 20th-century industrialization, the other from the pre-Columbian culture of America. First, let us remember the 1923 words of Henry Ford as he detailed the particular strengths of modern manufacturing techniques. He noted that production of the Model T required nearly 8000 distinct operations. But only 12% of those required “strong, able-bodied, and (practically) physically perfect men.” The remaining 7000 could be filled by men or women missing one or both arms, or one or both legs, or various digits, or having other deformities.

Second, let us remember the Aztecs, who lived in a region with a strict limit to the population it could support, and with no meat game to speak of, and yet who routinely nourished themselves on excellent meat—from their so-called “barbarous” sacrifices.

As we help foreign cultures to unlock the doors of consumption, let us remember that as the Aztecs and Henry Ford knew, value is a rich and fluid substance, and it is not always where it appears to be. And this is the greatest challenge as we strive, in this era of enlightened profit-seeking, to raise the bottom line of food management issues past the point of survival and comfort.

Post-speech narrative

When Andy called for questions at the end of his speech, a dozen hands immediately shot up like spears. Andy called on a woman who looked to be of Indian descent.

“Coming from a Third World country,” she said, “I found most of what you said really offensive. In your view, everyone is equal, but some are more equal than others. And who is to say whether people in the Third World even want a burger?”

“You know,” Andy said, “I sometimes find it in my heart to agree that cultures deserve equal consideration, perhaps to develop on their own terms. But we’re simply different. Culturally. We’re rich, they’re poor! And staying within the market’s logic, this is the most humane solution we can come up with.” Mike stood up in his McDonald’s uniform. “I’d like to answer a portion of that question as well, if that’s all right—and this answers the question about desire for the product. Our biggest growth areas are in fact in the developing world—so people do want the product. And I’ve brought a video presentation that demonstrates why.”

He inserted a videotape in the deck under the podium. On the screen appeared a McDonald’s interior in lavish 3-D animation; the mouth of a virtual woman was shown in close-up devouring a hamburger. “This here is a consumer in the First World eating a hamburger at McDonald’s,” Mike explained. The woman entered the bathroom and sat on the toilet. “This is a process we’re all familiar with,” Mike noted. “I don’t think I need to explain it to anyone.” The woman stood back up and closed the lid, which featured a Ronald McDonald face under a big “Thanks!” As the woman flushed, the video followed the plumbing underground into a system of tunnels.

“This is a standard piping system,” Mike narrated. “This isn’t unusual. We do this for oil. We could do this for food as well.” The underground tunnels whizzed past for a while, marked every few meters by the McDonald’s logo. “It’s rendered in this elaborate 3-D style because studies have shown that consumers are most responsive to this sort of animation right now, particularly in developing countries.”

The video followed the McDonald’s tubes back up to the surface. “Now, you can see the material emerging somewhere in the Third World, in another McDonald’s.” A big machine in the shape of Ronald McDonald discharged a lump of brown goo from its rear end onto a hamburger bun. “There’s also a filtering process, of course, not shown here,” Mike explained. “It’s completely hygienic." On the screen, a man in a turban was choosing his meal from the overhead menu. “Here, the Third- World consumer is choosing his meal. He can choose the number one, number two, number three, or number four, but instead of referring to combinations of food it refers to the number of times the product has been recycled. We can’t announce this publicly yet, obviously,” Mike explained. “But we want to be as transparent as possible and let people know what’s happening, at least in closed forums like this."

“And we’re lucky to be able to partner with the World Trade Organization, which has slightly different goals from ours. McDonald’s goals are to profit and grow, and we hope that we can provide a nutritious and tasty product in the process.”

“And our goals,” Andy said on behalf of the WTO, “are to help McDonalds profit and grow. And all other corporations as well.”

“Do you think the WTO is maybe lacking, like, a kind of human element?” asked a clean-cut kid in the back. “Have you ever seen starving people?"

“In pictures, yes!” Andy exclaimed.

“So tell me,” the student continued, "if you saw someone starving to death, don’t you think it might hit you in a sensitive place? Maybe then you’d think that markets and money and don’t mean so much—maybe feeding people means more.”

Andy nodded emphatically. “I must say that yes, there is a personal side to this, there are questions that we might very well have about this as human beings. But...”—Andy raised a finger to signal the essential point—“we at the WTO have a firmer grasp on theory than the average human, so we’re not quite as subject to this kind of emotion. As a result, we can direct world trade in a much more intelligent way—a theoretical way—in collaboration with our colleagues at the largest corporations.”

Afterwards, chatting with some offended students at the front of the class, Andy and Mike noticed that a bunch of students to their left were smiling. A few had dreadlocks, and one of them had a big handmade sign that said “KO the WTO.” He handed the sign to Andy. “Nice act,” the boy said wryly. “Y’all had me going for a good minute there.”

![[SLIDE 20/21/22]](/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_850px/public/2020-05/hamburger-Slide24.jpg?itok=zczN3gOa)