Hello. It’s truly a pleasure to be here among so many of the movers and shakers of the world economy. After all, it’s you guys who say what companies like mine can and can’t do. I know Barclay’s and Credit Suisse are here at the conference—you’re two of our largest shareholders.

I’ve been asked to talk today about critical success factors for establishing end-to-end payment standards, within a boundary of acceptable risk. I’d like to beg your indulgence, and broaden the scope of inquiry today, for these days, acceptable risk is very much on our minds at Dow. It’s a notion that has special application to end-to-end payments, but we’re now developing tools for handling risk in a wide variety of situations, of which end-to-end payments are only one special case. So allow me, if you will, to back up for a moment, and look at risk in its broadest sense.

Now risk is a very odd and ubiquitous beast. Risk at the chemistry level translates to risk at the level of consumer durables; that translates into risk in the supply chain, which dovetails cruelly with risk in the payments chain—feeding back into the cycle... a cycle that involves everything.

We all make risky decisions constantly. We eat chicken wings knowing we could choke on the bone. We cross the street knowing we could get hit by a bus—especially if we’re American and we’re looking the wrong way! Whenever there’s risk, we assess odds of catastrophe versus potential benefit—but we do it in an intuitive, “flying blind” sort of way.

Incredibly, we treat business risk the same way. We assiduously crunch numbers for labor costs, stock conditions, inputs and outputs, you name it; we even have whole conferences devoted to the cost of the payments cycle itself. But we make the biggest, riskiest choices the same way we choose what play to see in the evening.

Today, I’m here to tell you that a “flying blind” approach to risk is no longer possible—nor, as of May 1, will it be necessary. We'll help you to grab risk by the horns and wrestle it down to the ground all along the risk trail—with the beta version of Acceptable Risk, the world’s first market-smart risk standard. It’s a set of rules derived entirely from real-world risk cases and in line with best practices, that you can follow to maximize benefit for just about any project. We’re also providing a “Risk Calculator” to help you find out instantly what risks are or are not acceptable from a bottom-line business perspective—whether in end-to-end payments or anywhere.

Traditional AR

Before I demonstrate AR and the Calculator, I’d like us to stop and ask: what is “acceptable risk”?

For the government, it’s quite simple. When government evaluates risk vs. benefit, they basically just tot up casualties.

If a product results in one or two casualties, yet brings hug benefit in terms of lives saved, that risk can be deemed acceptable for the public good.

If the product kills dozens or hundreds, and brings little benefit, then that’s deemed unacceptable.

One flaw here, of course, is that profit never enters the picture. Yet profit is the reason we do everything that we do. Assessing risk without factoring profit is like trying to tune up your car without knowing where the engine is.

As a result of this blind spot, much of the government’s math is fuzzy. How many lives equal how much benefit? Where’s the tipping point? Making this explicit would of course mean putting a precise value on human life. The government can’t do that, and of course nobody else can either. The good news is nobody has to, because our society has a democratic means for determining value. It’s called the market, and it plays no favorites.

Over the past few decades, our society has substituted the “invisible hand of the market” for government monopoly over many aspects of life, from fighting the war on terror, to operating schools and prisons, to taking care of our parents in their dotage. The same has been true for risk management.

Up until 1974, whenever we wanted to market a product in the US, we had to prove to the government that the product was safe. That all changed when after one particular fight over a pesticide component we were producing, the government agreed it would assume the burden of proving the product’s danger.

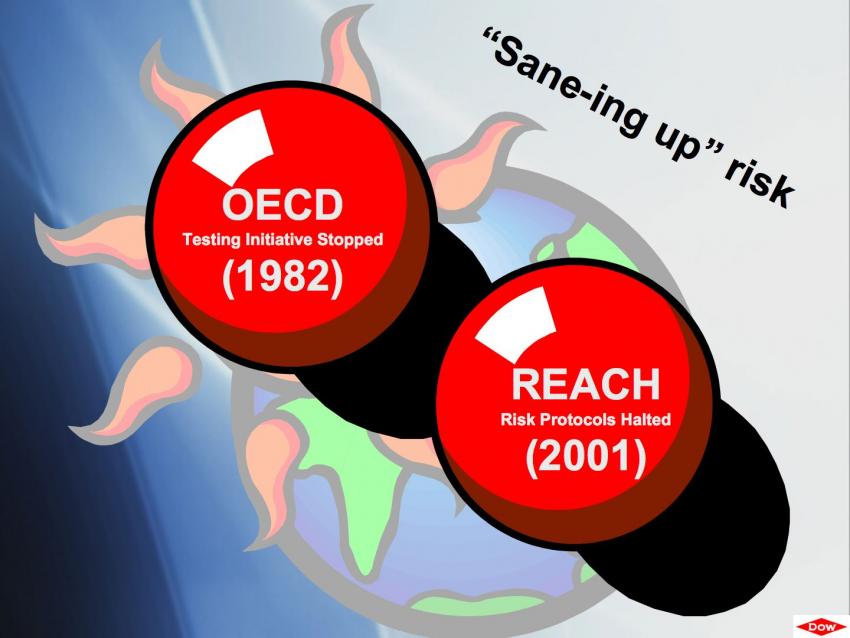

The government basically said: go ahead, use your best judgment, and if we really have to, we’ll tell you to stop. Today, we’re gratified to see this new paradigm formalized in the WTO, which makes governments prove that products are harmful, rather than producers prove that they’re safe.

In this and other ways, we at Dow feel that we have been instrumental in “sane-itizing” the global risk picture. After all, where consumers and corporations have their own eyes, ears, and brains, is it really necessary for governments to provide extra ones?

New Model AR

Amazingly enough, though, there is still no tool to help us in business know what risk is acceptable, and what isn’t. We stumble along with our unspoken rules, hoping against hope our decisions make sense.

Dow Acceptable Risk will change all this. For the first time ever, you will know beforehand what you can and can’t allow to occur. Will project X be just another skeleton in the closet—something your company comes to regret? Or will it be a golden skeleton—will it have harsh, but acceptable costs?

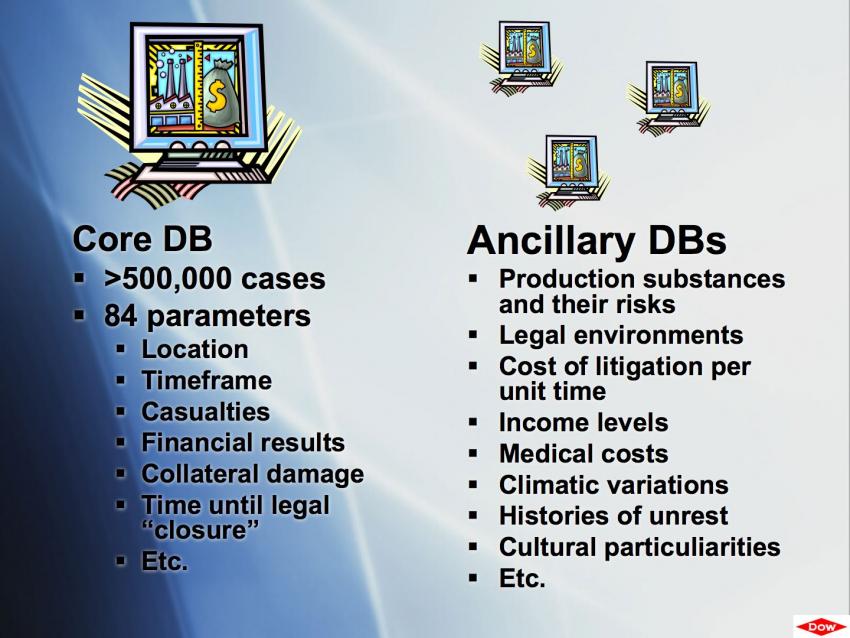

To help you determine this, the AR Calculator accesses an immense knowledge base of over half a million risk events from every country on earth (reflecting the global risk breakdown). These cases are normalized according to location, time, casualties, financial outcome, litigation costs, and other parameters. 26 ancillary databases on products, laws, climate, income levels, etc. further clarify what any given case will mean in bottom-line terms.

At the highest level, event data have been divided into four core types.

Type 1: Unproven Harm / Diffused Risk (UHDR)

The most common type are those cases where harm shows up late, if at all, and investments are amortized through wide distribution.

Beginning in 1972, for example, alarmists began linking casualties to one of our pesticides, Dursban, whose main ingredient came from German nerve agent research in WWII. Studies on student volunteers as late as 1998 showed no unexpected results, but Dursban lost out and was banned in the US. Its usefulness continues, fortunately, [click: maps] in places with more rational approaches to risk.

Had we had Acceptable Risk back in 1972, we would have known that Dursban’s global potential, combined with low chances of major risk "blossoming," would mean that if Dursban was going to be a skeleton in the closet, it would be a golden one—which it is.

Type 2: Mitigated Causality / Indirect Ownership (MCIO)

A type of risk especially familiar to bankers is when the company involved is the agent of another entity who is primarily responsible.

Close to home for Dow in this category are some products that helped cause wide and sometimes illegal devastation in wartime Vietnam. We got a lot of flak in the media for these products, but it never got worse for that, mostly because the ultimate culprit was the US military. Today, napalm and Agent Orange are definitely "skeletons in the closet" for us. But even in 1970, AR would have shown us that these skeletons would likely be golden.

A more complex case is IBM’s sale of technology to WWII Germany for use in identifying Jews. This was bad. But IBM's early management could have seen that the risks here would be mitigated by (a) uncertainty about what the technology would be used for; and (b) the likely distance in history from which judgment would happen, if it ever did.

Some people would say that IBM’s decisions in this matter were lucky, others would say they were shrewd. But no one can deny they were profitable, and although this issue remains a skeleton in the closet, in retrospect it is quite clearly golden.

Type 3: Marginal Target / Unclear Impact (MTUI)

You may have heard the joke: How many Americans does it take to screw in a lightbulb? 12: one to climb the ladder and 11 to file the lawsuit. What about Indians? Oh, just one!

This joke could well be about those cases in which regional differences in law, culture, income, and so on produce radically different risk outcomes. I’d like to illustrate this with a hypothetical use of the AR calculator.

Suppose Bill wants to set up a factory to produce a new pesticide. He logs on to the AR calculator and plugs in the various chemicals, how much he wants to produce, and so on. The database finds roughly analogous cases, adjusts for geography and changes in law and income, and tells Bill that the risk of setting up in the US might well involve over $2 billion in liability rom potential area lawsuits. After comparing that with profit projections, it's very clear that taking this route will basically suck.

But the database proposes alternatives. The harm risk in India, for example, translates into potential losses of less than $400 million, based on previous liability settlements. Meanwhile, profit margins actually increase thanks to cheaper manufacturing, less draconian inspection requirements, etc. It is clear already that the skeletons here will be golden.

As it happens, this case is typical of the type where risk acceptability varies depending on cultural and societal conditions. We would of course never wish to imply that an Indian life is worth any more or less than any other. I myself believe in the sanctity of life. But the market has its own logic, and if we’re going to live with it, we must make the most of its choices.

That said, the Acceptable Risk paradigm is no magic bullet, and cannot fix everything. The Bhopal catastrophe of 1984 was so extreme that risk adjustments just wouldn't have mattered. It’s good it happened in India and not in Vermont, but even if it had happened in the Congo, there would have been huge market stress. Dow is gratified by the SEC’s recent ruling that shareholder pressure groups can’t interfere with the way we approach such ongoing problems, but that certainly doesn’t make these skeletons golden. Before embarking on any enterprise with such huge potential effects, we must weigh the factors by hand very carefully.

Type 4: Uncertain Provenance / Diverse Agency (UPDA)

That said, we can’t be simplistic about hugeness, either. It's not the number of skeletons in the closet, but what they represent.

An extreme case in point would be the Green Revolution, the introduction of modern technology in Third World agriculture in the 60s and 70s. Just for the sake of illustration, let’s give momentary credence to the most pessimistic figures and suppose that between 1970 and 1990, the number of hungry folks in the world did grow by 11%, and that the Green Revolution had something to do with it.

Would this be acceptable risk from our viewpoint? The answer is clear when you notice, on the one hand, that the Green Revolution was essential to modern agribusiness, being its most profitable experiment ever; and that, like climate change and other huge trends, the Green Revolution belongs to a type of risk case in which scientists do not all agree on the source of problems caused, or whether they even exist. Unless the precautionary principle comes to dominate government once again, there is little actual risk in such cases—especially interesting now at the dawn of the new “Green Revolution.”

A Sobering Note

Today, as we make sure market-based values guide our decisions, we have to constantly watch out for those who would establish risk guidelines that aren’t so useful.

One group of challengers are those pressure groups within government who would have us return to the 1970s and the precautionary principle.

Then there are the so-called “socially responsible” investment groups, a “fifth column” who put emotional pressure on other investors to completely avoid all skeletons—bypassing many opportunities in the process.

Finally, the battle is far from won at the international scale, either. Yes, a global reach has made flexible risk management easier; yes, the WTO and even the EU do prioritize profit in a way that we all find sensible.

But there are other global projects as well. The UN’s Human Rights Norms For Business would essentially let governments and NGOs make sure business actions accord with old frameworks. As far as we’re concerned, adopting these Norms would be attaching leg irons to a prize horse.

CLOSING REMARKS

Now because you’re one of the very first audiences to discover Dow Acceptable Risk, we’d like to offer each of you the opportunity to discover for yourself just what it can mean—whether in end-to-end finance or anywhere. That’s why anyone here who wishes to will receive, free of charge, a Concurrent Use license for a full year of use of the Risk Calculator. It’ll help you and your corporation by letting you access the enormous AR knowledge base as a help for decisions.

We also want to offer you some free keychains.

So after questions please come up and give us your business card so we can send you the software keys you’ll need to get started with the risk calculator. As you use it, we’d appreciate if you gave us feedback on anything you’d like implemented in future versions and let us know of any cases we may have neglected to include in the standards.

And now the part of the day that I’ve really been looking forward to. A lot of you have probably been wondering what’s under this shroud. Well, you’re about to find out.

Because if there’s one thing we want you to remember from this talk, it’s that “the only good skeleton is a gold skeleton.”

["Vikram" (Mike), wearing a hardhat, pulls off the cover of Gilda, the golden skeleton, in a bang and puff of pyrotechnic smoke.]

Meet Gilda, the mascot for the Dow Acceptable Risk program.

Do you have a skeleton in the closet? A lot of us do. But maybe the problem isn’t the skeleton, maybe the problem is the way you’re seeing that skeleton.

It may be just a skeleton in the closet, yes—but it could very well be a golden skeleton too.

And as you move into a future of ever-increasing complexity and ever-increasing opportunities, Dow Acceptable Risk can assure that your touch will a Midas touch, and that all that glitters will henceforth be gold.

As James Jeffrey Roche wrote one hundred years ago:

I’d rather be handsome than homely;

I’d rather be youthful than old;

If I can’t have a bushel of silver

I’ll do with a barrel of gold.

So thank you very much; we hope you come up and get a closer look at Gilda, get your picture taken with her, whatever. I’ll take questions now, but afterwards I want to remind you to get your free keychain, and drop off your business card if you want to sign up for the free license for a year of AR use.

So, any questions?

[There were questions, as well as interactions with audience members afterwards; see the video excerpt.]