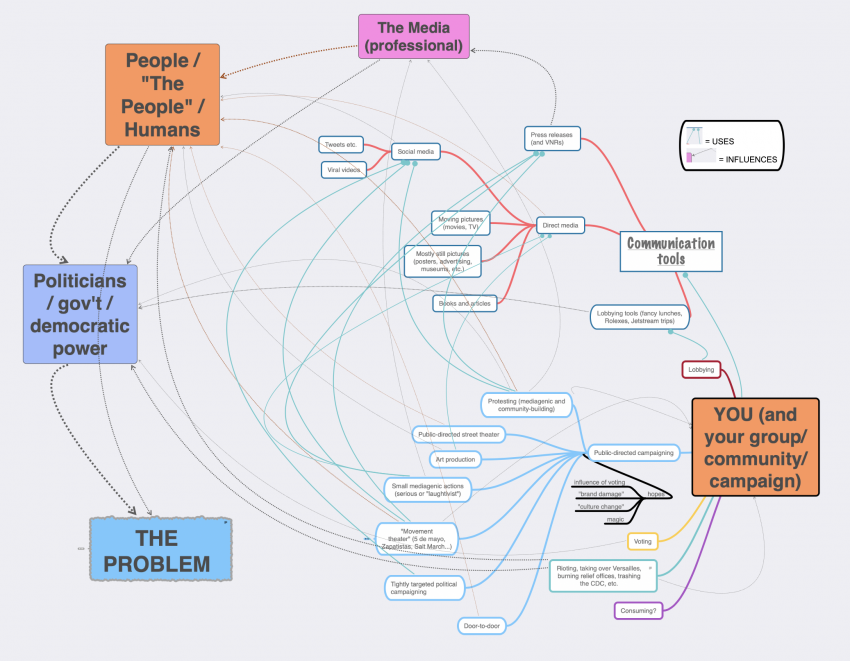

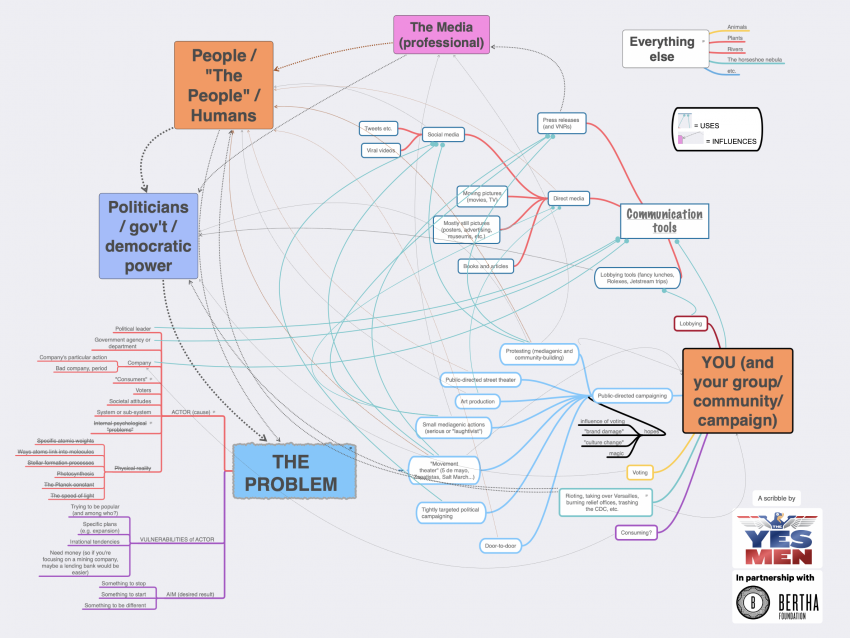

Below is the kind of diagram we sketch out on the fly, with their particular project in mind, getting them to try filling in the blanks between them ("YOU") and the result ("THE PROBLEM").

To get deeper into the nitty-gritty of it, the best workbook we know is The Path of Most Resistance, by Otpor and CANVAS co-founder Ivan Marovic. (Otpor helped overthrow Milosevic in 2000 and CANVAS went around teaching others how to handle their own dictators. Ivan himself was the impetus behind our "Brokers and Police" action during Occupy Wall Street.)

The Problem

The first elements of the universe are just "You" and "the Problem." It's a problem, you're a group or campaign. Simple.

Ways the Problem gets fixed (in a democracy)

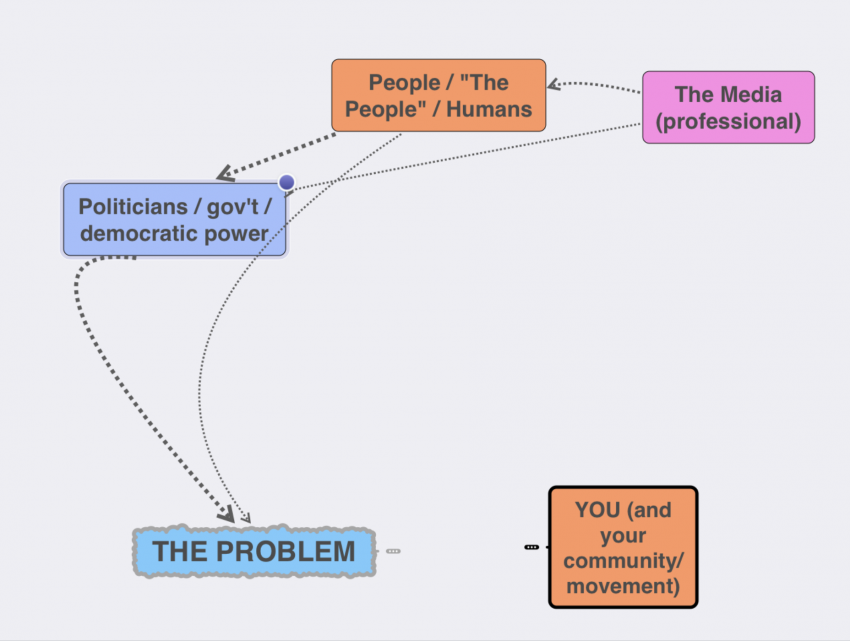

In a democracy (or approximation thereof), the government must respond to "the People," who respond to messages that often (but not always, as we'll see) come through the media.

"The People" can sometimes affect a big problem directly—like, in a non-democratic situation, through one huge collective action—but more often change comes indirectly, through legislation or regulation (which are also collective, unlike "consumption"—more on that later).

How can you intercede?

There are a few ways that you (a subgroup of "the People" of course, but for our purposes split off to the side) can help solve the Problem—either directly or, more often, via Politicians, the People, and the Media.

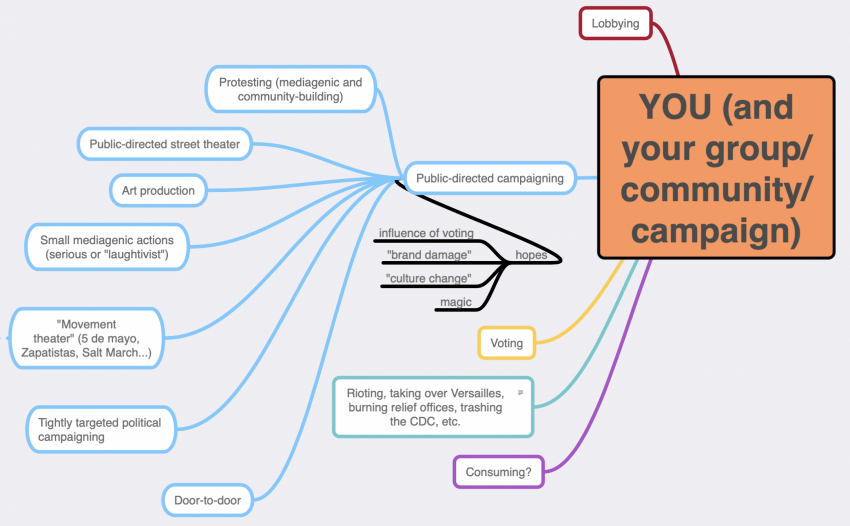

We'll focus especially on the "public-directed campaigning" node, where campaigners, protesters, and "results-oriented artists" fit in. As you might guess from the "public" part, the audience here is "the People" (q.v.).

Tools we can use

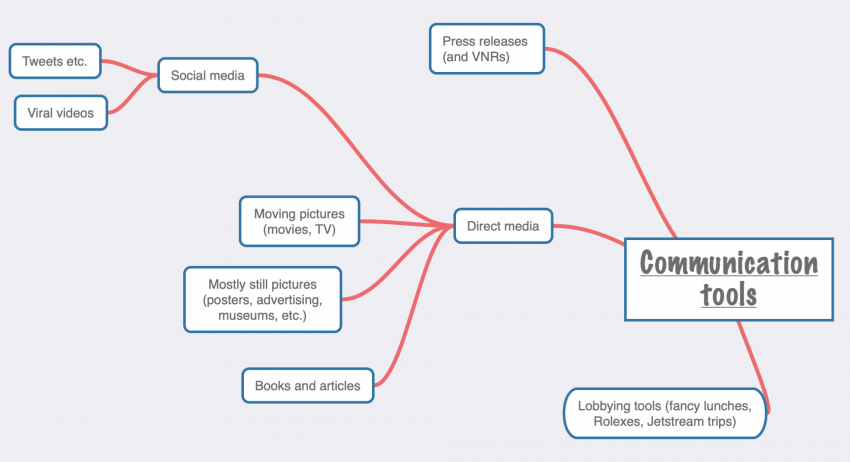

Anyone trying to move People, for good or evil, needs tools to do so. Here are some of those tools. (We're focusing more on what you with your budget can use, rather than they with theirs, so we're lumping "advertising" into "still pictures," just so we mention it, and ignoring all of its other forms. If only this were reality!)

And here's where it starts looking complicated. But it's not.

Obviously, each tool you can use will reach a different audience or audiences. That means tons of lines in this diagram—but it's actually pretty simple. (It's even simpler for a dictatorship. Then, you're going have few if any lines to politicians, and the line from People to Problem will have to be very thick indeed.)

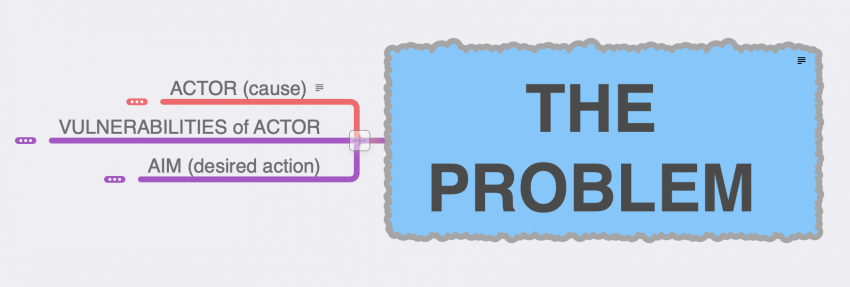

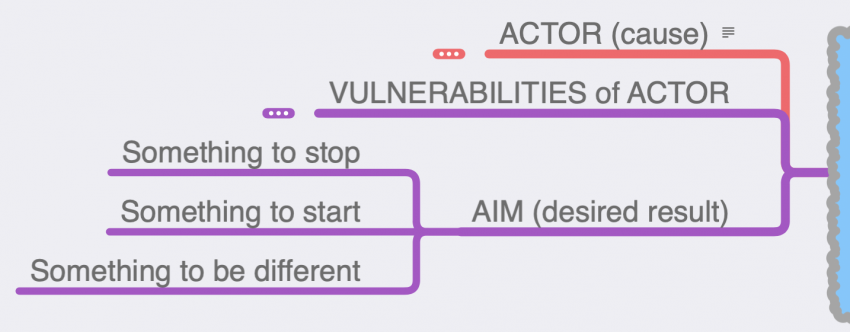

Here's where it does get complicated.

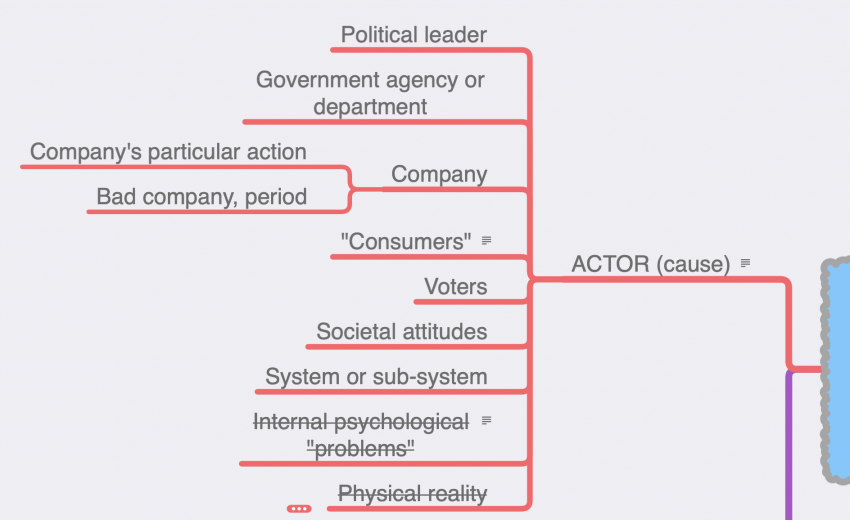

Analyzing the actual problem you want to solve—and who can possibly solve it—is where it actually does get pretty complicated. But if you're thinking through a campaign, and how individual actions might help within it (besides "raising awareness"), you do have to do this part: you have to figure out who's your main actor (i.e. target), whether they're vulnerable (if not, pick a different actor), and what exactly you might want them to do.

This is tricky, and to be honest we Yes Men have often skipped over it. Like many activists, we've replaced precision in this part with a big leap of faith: if we get people angry enough in a certain direction, things will probably change. And sometimes that's right! But unless the campaign you're part of is big enough (see below), trusting "awareness" is inefficient at best, and useless at worst.

Problem analysis

The best, most effective actions have a problem analysis, or are part of a bigger campaign that does.

You can start with the AIM—to get a company to stop blowing up mountains, for example, or the police to stop murdering black people. (It's fine to revise the AIM as you go along. Send cops to prison? Why not defund the police. Defund the police? Why not fund free education. Fund free education? Why not imagine a society in which everyone has what they need, and in which violence of any sort begins going extinct, instead of the thousands of species our system is killing....)

In any case, at some point you need to decide which ACTOR is causing the problem, and how you might want to muster public opinion against them. (It's fine to revise this as you go along, too. A police station might make a fantastic first target—and burning it down might be just the right image to communicate far and wide—but to make the police stop causing the problem, other ACTORs might need to be targeted: local, state, and national legislators, for example, who can pass laws defunding police departments and putting those budgets elsewhere.)

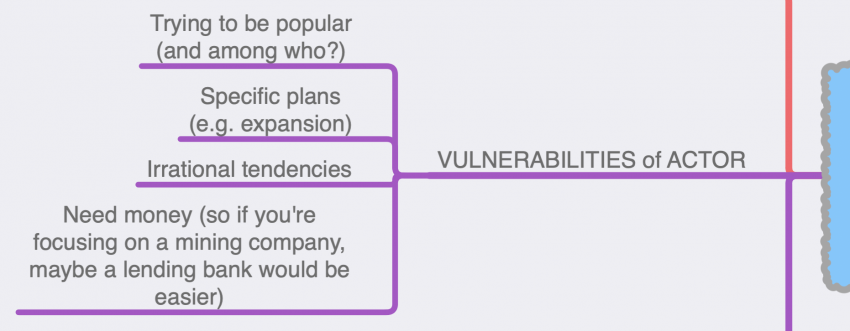

Finding the vulnerabilities

Once you've picked the bad actor, you'll want to look at their vulnerabilities. One great example of how to do this is provided by an activist group that managed to stop all banks from financing mountaintop removal coal mining.

Initially, the group focused on the mining companies themselves—before realizing that those companies, themselves, were pretty invulnerable to public opinion; they just didn't care.

So next they turned their attention to the banks that financed those companies—and they found that one particular bank, PNC, had a lot of vulnerabilities: their business model relied heavily on bringing in college students as clients!

So the activists went to campuses and campaigned heavily against PNC—and a steady barrage of actions later, PNC divested from blowing up mountains. It's a long story, but all other banks eventually followed suit—meaning that mountaintop-removal coal mining, while still occurring in 2020, is on its way out. Thanks, activists!

(You can read about this and other super-strategic and super-effective actions on Actipedia; most of these needed a very thorough problem analysis, even if they didn't call it that.)

In summary

If this diagram (in full below) is overwhelming, ignore it! Sometimes, with a big enough campaign (e.g. the police-violence example above), strategies for change evolve collectively—or, rather, strategic thinkers step up and do the thinking-through work at key moments.

That's one great reason it's fantastic to join up with a campaign or movement and make yourself useful within it. But if you're a lone wolf and just want to do your own thing, just keep in mind: "raising awareness" is not enough! You'll have to give it a bit more thought than that.

Download the complete PDF of the diagram here. For further reading on theories of change and on thinking through strategy, see the "strategy" part of our resource guide.

A few extra notes

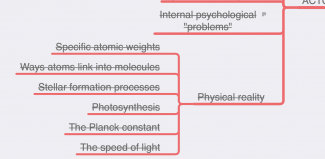

THE PROBLEM

If you're thinking that the big PROBLEM is some kind of psychological thing—like "gullibility" or "laziness" or whatever—you might as well blame the Planck constant. That's why we've crossed both of these out as ACTORS to worry about.

CONSUMING AS ACTIVISM

There's a shortcut to avoid all this apparent complexity: it's the line in the diagram that goes from "consuming" to "a company." So simple! Whereas all the other means of affecting things are indirect—you -> media -> voters -> government -> company—that one cuts straight to the problem.

The only problem is that it just doesn't work, not even a little, and fits right into the capitalist status quo like a tiny foot in a big ugly sock. So unless your consumption behavior is part of a super-well-coordinated campaign, don't even think it's going to do more than save that one chicken—which, admittedly, isn't nothing.

EVERYTHING ELSE

One last thing: there's an element up in the top-right part of the diagram—"everything else"—that it's our job to enjoy in as non-destructive a way as we can. That, in fact, is the whole point of the exercise. So enjoy!

With special thanks to Marcial Godoy.